Digging deep: Detroiters work to clean up city's toxic soil

Nina Ignaczak |

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Wayne State University urban geology professor Jeffrey Howard knows Detroit dirt. As a teacher and researcher, he's been digging into Detroit's vacant land and industrial sites over the last several decades in an effort to better understand and classify the city's soils, many of which are disturbed and contaminated as a result of the city's industrial legacy.

His efforts have produced maps and descriptions of the soils in the city. And the patterns of contamination he finds are often a representation of the city's history. One case involves a surprising household appliance.

"Detroit was famous for making stoves," says Howard. "If you go to Henry Ford Museum, you can see all the different kinds of stoves they used to sell here. They would burn coal in those stoves in homes from the 1800's until the '20s or '30s.

"You'll find coal, coal ash, or coal cinders," he adds, "which is stuff that accumulates inside the stove or a boiler. You've got to rake it out of there, so you see a lot of coal cinders, pieces of coal, coal related waste all over the place."

All this toxicity in the soil can make its way into the food we eat and water we drink, causing serious health and developmental problems, especially for children. Fortunately, Howard is one of a handful of people and organizations working to understand how contaminated Detroit's soils are, and how best to restore it.

This work is essential to a city intent on growing its own food.

The extent of the problem

Jeffery Howard, WSU Geology professor

Jeffery Howard, WSU Geology professor

Industry, not surprisingly, is a major culprit of contamination in Detroit.

"You see a lot of fly ash deposited in soil from industrial areas," says Howard. "It's mainly concentrated in southwest Detroit, as you can imagine, where all the heavy industry is."

Lead and arsenic are also ubiquitous. The arsenic is naturally occurring, but lead, says Howard, "mainly comes from burning leaded gasoline back in the day. Of course it's still there today."

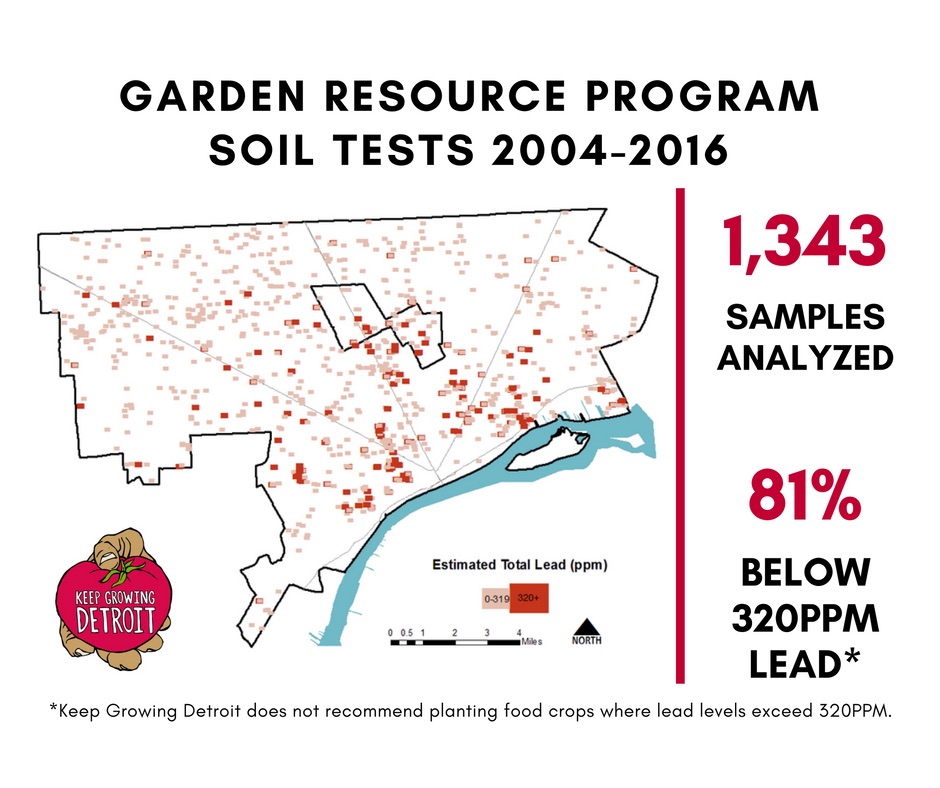

Keep Growing Detroit (KGD), a nonprofit that supports food sovereignty in Detroit, has been measuring and maintaining a database of soil contamination in urban farms and gardens across the city for the pasts several years. KGD co-director Ashley Atkinson says her organization's data show that fewer than 19 percent of soils sampled from Detroit urban gardens and farms contain levels that exceed contact standards. But she also recommends people consider the historic land uses of a site when planning their gardens.

"When people are looking to create farms and they want to test the soil, they need to watch where they are on the property, and what were the previous uses at that location," says Atkinson. "Generally, where the yards were, the soil's good. But where abandoned or demolished houses were, there can be more contaminants. If you really want to know what's in your soil, it's helpful to be a little thoughtful about where you do your testing."

Atkinson also points to preliminary evidence collected by the organization that points out how the act of farming sustainably and enriching organic matter can help restore the soils.

"The more organic matter that you have in the soil, the less bioavailable most contaminants are, so they're less likely to be in plants and have contact with humans," she says. "And with regard to drainage and stormwater management, the more organic matter, the more soil porosity, the more holding capacity for water the soil will have."

"When people are looking to create farms and they want to test the soil, they need to watch where they are on the property, and what were the previous uses at that location," says Atkinson. "Generally, where the yards were, the soil's good. But where abandoned or demolished houses were, there can be more contaminants. If you really want to know what's in your soil, it's helpful to be a little thoughtful about where you do your testing."

Atkinson also points to preliminary evidence collected by the organization that points out how the act of farming sustainably and enriching organic matter can help restore the soils.

"The more organic matter that you have in the soil, the less bioavailable most contaminants are, so they're less likely to be in plants and have contact with humans," she says. "And with regard to drainage and stormwater management, the more organic matter, the more soil porosity, the more holding capacity for water the soil will have."

That's important as Detroit works to reduce the impact of stormwater runoff on its aging combined sewer system.

The benefits of clean soil

Restoring soil is also important as a way to combat climate change.

"Soil has a huge power for carbon sequestration," says Atkinson. "There's no more carbon in the world today than there was previously, but now it's in the atmosphere and in the ocean, when it used to be is in the soil. We've had such devastating impacts on our soil over time that we've made carbon available when it shouldn't be, and that's why we're having this increase in temperature.

"There's so much benefit for treating the soil well."

Akello Karamoko, a KGD farmer, says the work of restoring soil is underappreciated

.

Akello Karamoko sitting on KDG's compost pile

Akello Karamoko sitting on KDG's compost pile

"Doctors and lawyers can't do anything for the soil because it's not in their job description," says Akello. "Farming and gardening is one of the few professions where you get to use sustainable practices like cover crops and rotation to help build the the soil."

And restoring that soil, acre-by-acre, is critical to reaching a goal of having a city that grows its own food.

"If we want to become a food sovereign city, all of the food needs to be grown here and we have to work with what we have," he says. That means planting around areas of contamination while rebuilding soil with compost to increase biological activity, build soil structure and stability, and enhance the soil's ability to hold air and water.

Undoing the damage

Thomas Wackerman, president of ASTI Environmental

When it comes to development in Detroit, soils have to either be remediated or contained on site. According to Thomas Wackerman, president and founder of ASTI Environmental and practice leader for the firm's brownfield redevelopment group, one of those options makes much more sense.

"In today's world, what we try to do is implement control, rather than remediation, because there's not much of a point for taking soils from property 'A', and dumping them in a landfill on property 'B'," he says. "That doesn't really solve anything. We try to maintain stuff on site as much as possible."

Control is typically doable, except when a soil contaminant exceeds direct contact standards established by the State of Michigan. In that case, nobody should be touching it, and engineering workarounds, like placing concrete or asphalt over a clean fill barrier, are needed to prevent human contact.

Another difficult situation is soil vapor intrusion into buildings from contaminated soil and groundwater. Depending on the concentration of contaminant and the location, this can sometimes be addressed with a vapor barrier under the envelope of the building. More intense situations may require a a collection system.

Compounding this problem, a range of contaminants in Detroit soils can create this vapor.

"It depends on what part of the city you're in," says Wackerman. "If you're down along the riverfront, for example, there was a lot of industrial fill that went on starting in the 1800's, and you can find just about anything.

"It's very heterogeneous because it came from all kinds of different sources. In general, the issues of lead-based paint, the issues of leaded gasoline, the issues of lead being ubiquitous in products for a very long time, probably makes lead the number one things you can almost count on. The number two thing you can almost count on is petroleum products, oils, gasolines, things like that."

Thomas Wackerman, president of ASTI Environmental

When it comes to development in Detroit, soils have to either be remediated or contained on site. According to Thomas Wackerman, president and founder of ASTI Environmental and practice leader for the firm's brownfield redevelopment group, one of those options makes much more sense.

"In today's world, what we try to do is implement control, rather than remediation, because there's not much of a point for taking soils from property 'A', and dumping them in a landfill on property 'B'," he says. "That doesn't really solve anything. We try to maintain stuff on site as much as possible."

Control is typically doable, except when a soil contaminant exceeds direct contact standards established by the State of Michigan. In that case, nobody should be touching it, and engineering workarounds, like placing concrete or asphalt over a clean fill barrier, are needed to prevent human contact.

Another difficult situation is soil vapor intrusion into buildings from contaminated soil and groundwater. Depending on the concentration of contaminant and the location, this can sometimes be addressed with a vapor barrier under the envelope of the building. More intense situations may require a a collection system.

Compounding this problem, a range of contaminants in Detroit soils can create this vapor.

"It depends on what part of the city you're in," says Wackerman. "If you're down along the riverfront, for example, there was a lot of industrial fill that went on starting in the 1800's, and you can find just about anything.

"It's very heterogeneous because it came from all kinds of different sources. In general, the issues of lead-based paint, the issues of leaded gasoline, the issues of lead being ubiquitous in products for a very long time, probably makes lead the number one things you can almost count on. The number two thing you can almost count on is petroleum products, oils, gasolines, things like that."

A broad fork used to aerate soil

A broad fork used to aerate soil

And containing or removing these contaminants makes development in urban areas like Detroit more complicated and costly than in so-called greenfield, suburban areas without a history of industry.

"You go out and you do your assessment, and that costs money," says Wackerman. "Then you go out and you fix the things you found, and that costs money. All of a sudden you have a higher cost of doing business than you would in a greenfield. Then you're moving along and all of sudden you find some historical operation that you didn't know was there, that's caused additional contamination. It brings everything to a halt, you got to figure out what's going on, you have to fix it, then you can move on again. That's why it's more complicated to build on urban sites."

These costs and complications are the reason for "brownfield" laws and programs to help cities and developers address contamination issues.

"The extraordinary costs are not just limited to environmental issues, they can have to do with depressed markets, cost of doing business, and high tax-rates," Wackerman says. "We have tools such as tax abatements, tax increment financing, and the Michigan Strategic Fund. Anything that assists in leveling the playing field, to make it cost the same to build in a city with all of it's environmental and non-environmental problems as it would be to build out in the suburbs."

This piece is part of a series highlighting the role science plays in Detroit. It is supported by the Michigan Science Center.

All photos by Nick Hagen.